Interrupting Infinity Exclusive Commentary. © 2012 by David St.-Lascaux

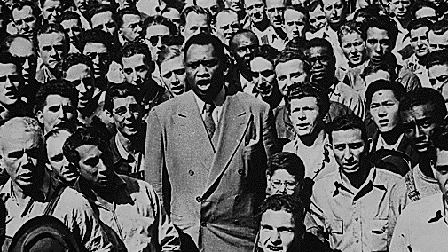

Still from Paul Robeson: Tribute to an Artist (1979), USA. Image courtesy the Criterion Collection (permission pending).

EDUCATION IS A GOOD, AND OFTEN RARE THING, especially in a society in which the dissemination of information is controlled by consumer capitalist corporations, and historical facts are inconvenient. In America, for example, there is almost complete media silence about just about everything that matters in favor of distractive consumertainment. So it’s no wonder that product placement agencies refused to cooperate with Morgan Spurlock as he set out to fund “POM Wonderful Presents: The Greatest Movie Ever Sold.” As important as Spurlock’s contributions are to awareness of the pervasiveness of drivia (drivelish trivia), they are liteweight compared to those of the late, great genius who was Paul Robeson (1898-1976). A small theaterful of people were recently privileged to see a 30-minute, 33-year-old tribute to the man and his life, which is no doubt fine with the U.S. Government. The film: The Academy Award winning Paul Robeson: Tribute to an Artist, directed by the late Saul J. Turell and narrated by Sir Sidney Poitier, recipient of the 2009 Presidential Medal of Freedom (bestowed by Comrade Barack Obama).

Robeson’s achievements were stunning and singular: overcoming racism at Rutgers (1915-19) to achieve football status as an All-American (of which he was later stripped and which was still later restored), Phi Beta Kappa and more. In a 1928 theatrical production of Show Boat in England, Robeson, as Joe, sang Jerome Kern’s and Oscar Hammerstein II’s immortal “Ol’ Man River,” including the word “niggers.” Robeson became the first black Othello playing against a white Desdemona (the stills of the role’s Great White Actors in blackface, including Sir Laurence Olivier, are self-inflicting).

A genius and activist who resolved to “keep on fightin’ until I’s dyin’,” which he did.

Robeson became political early on, supporting the Republican soldiers during the Spanish Civil War; following Pearl Harbor, he acted as a patriot in singing to support the war effort. After the war, he was an advocate for both racial justice and communism, singing Mao Zedong’s People’s Republic of China’s national anthem in a performance in Europe in 1949. As a result of Robeson’s rose-colored anti-imperialism, the State Department revoked his passport in 1950, not returning it until 1958, in an ironic, if consistent act of American totalitarianism against freedom of expression about matters economic.

The film’s most disheartening moment, for a naïve Northerner, was the footage of the Peekskill Riots (as in whites and New York State troopers attacking Robeson concert attendees with rocks and baseball bats) in 1949, in which white New Yorkers most resemble their stereotypical Southern counterparts of the Martin Luther King, Jr., Fifties and Sixties, the hatred proverbially radiating from the whites of their eyes.

The film omits Robeson’s flaws. Poitier mentions neither his marital infidelities nor criticizes his dishonest support of Soviet totalitarianism (his rationalized counterweight to the right’s Orwellian, propagandistic disinformation about him). His strange hymnic celebration of Mao’s revolution is surreal in its own naïvété, though hardly more so than America’s capitalists’ indebtedness, and financially treasonous betrayal of America’s workers to our former-but-apparently-no-longer-unless-one-considers-the-profitable-promise-of-war-against archenemy Third Way China.

Ultimately, Robeson would be vindicated in race if not his choice in leaders. America’s leaders, including those of the Civil Rights movement, let him down, bowing to McCarthy-era hysterics, actually a continuum of suppression that marches on today. Meanwhile, out on the streets, American blacks have seen half their wealth erased in the last half decade as their ranks swell the unemployed and for-profit prisons, and plutosocialism is alive and well among financial and corporate welfare queens.

Despite the courageous efforts of such movements as Occupy Wall Street, modern history seems to suggest that it’s futile and pointless to fight the forces in power, whichever they might be. Robeson, on the other hand, was a man of courage – of conviction and action. For him, it was pointless not to “keep on fightin’, until I’s dyin’,” which he did. One is reminded of fellow darkie (the equally offensive word that “nigger” was changed to in a later rendition of “Ol’ Man River” in Show Boat) Langston Hughes, in “Let America Be America Again” (1938; full text here):

I am the poor white, fooled and pushed apart,

I am the Negro bearing slavery’s scars.

I am the red man driven from the land,

I am the immigrant clutching the hope I seek –

And finding only the same old stupid plan

Of dog eat dog, of mighty crush the weak.

I am the young man, full of strength and hope,

Tangled in that ancient endless chain

Of profit, power, gain, of grab the land!

Of grab the gold! Of grab the ways of satisfying need!

Of work the men! Of take the pay!

Of owning everything for one’s own greed!

. . .

Sure, call me any ugly name you choose –

The steel of freedom does not stain.

From those who live like leeches on the people’s lives,

We must take back our land again,

America!

O, yes,

I say it plain,

America never was America to me,

And yet I swear this oath –

America will be!

Out of the rack and ruin of our gangster death,

The rape and rot of graft, and stealth, and lies,

We, the people, must redeem

The land, the mines, the plants, the rivers.

The mountains and the endless plain –

All, all the stretch of these great green states –

And make America again!

* * *

Paul Robeson: Tribute to an Artist will also be screened at MoMA on Friday, February 10, 2012, at 4:00 p.m. The film is also available from the Criterion Collection at this link.

* * *