Interrupting Infinity Exclusive Commentary. © 2012 by David St.-Lascaux

Elizabeth Streb’s “Kiss the Air!”

Park Avenue Armory, December 14-18, 2011

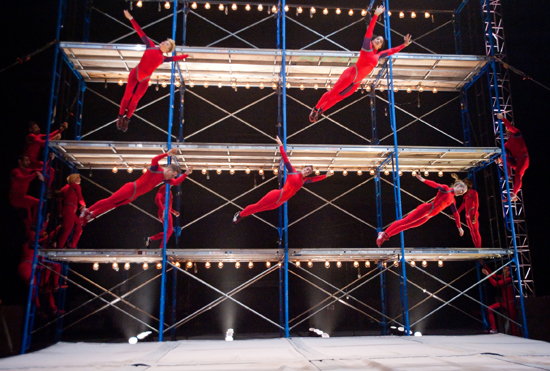

Elizabeth Streb’s company in “Human Fountain” in “Kiss the Air.” Photo by Stephanie Berger; courtesy Resnicow Schroeder Associates.

IF YOU CONSIDER YOURSELF A MEMBER OF THE CULTURATI, you probably don’t consider yourself an aficionado of populist spectacle. You haven’t attended cage fights or World Wrestling Entertainment bouts; you haven’t spent your precious time watching American Gladiators or Fear Factor; you’ve been too otherwise occupied to attend the Spiderman and X-Men superhero movies; and you somehow find yourself able to resist the addictive allure of steroidal, pseudo-immortality-conferring electronic games.

Elizabeth Streb mayn’t subscribe to that stuff, either, but she’s got the same DNA, infused from the startlingly similar culturato analogs to the above-mentioned bread and circus: the parallel universe of the intelligentsia’s “anti-intellectual aspect of motion” (noted by Streb in an interview in BOMB with A.M. Homes) as practiced by her hero Chris Burden, Marina Abramović and choreographer Trisha Brown. Streb likes extreme physical action, and she so-brands her own version “POPACTION.”

Streb’s genius and showwomanship were recently on display in “Kiss the Air!” at the Park Avenue Armory as part of the Armory’s three-dance program (the others being Shen Wei and Merce Cunningham). The program required multiple takes, given that the first take—the experience of watching “Action Architect and Choreographer” Streb’s company perform—was essentially one of passively sitting slackjawed for one-and-a-quarter hours. The second take—one of comprehension—required heavier lifting.

“Kiss the Air” no doubt represented Streb’s most elaborate production to date, and it appeared to have been purpose-built by Streb and Hudson Scenic for the Armory, which is emerging as one of New York’s best performance venues. The show ranged along a five rectangular “ring” circus layout, beginning at one end, moving to the other, and closing center ring in a dramatically awaited green glasslike pool. The show’s mainstream production was reflected by the burly, booming DJ/MC Zaire Baptiste, wearing blue-white LED’s along his body; David Van Tiegham’s relentless, adrenaline-and-tension-inducing primetime soundtrack; cinematographer Alex Rappoport’s six rafter-hanging big screens fed by roving video camera operators; and the amplification of the performers’ belly-and-backflop-on-mat dull thudding falls. The performers themselves were comic book sculptures, dressed in Andrea Lauer’s supersaturated red bodysuits, smiling and amped.

So was it dance, or art? It was, without debate, strebbing—the wall-crash gerund that Streb’s name has famously become.

The individual segments had names evoking Streb’s thematic approach, including “Catch,” “Falling Sideways” and “Ascension.” The first piece, “Enter,” a warm-up, featured three rows of performers in a variety of gymnastics, including free-standing flips, hands-free forward rolls, and a series of flying-ring, trapeze-like tours de force. In “Instant Flight,” performers were launched by opposing pairs of air-powered catapults to achieve acrobatic landings. “Swing” utilized Jeff Becker’s rotating, centrally pivoted ladder—a centrifuge seesaw with which up to six performers elegantly interacted at a time. “Human Fountain” was the most disconcerting: over a dozen performers dove from a three-tiered “truss” scaffolding to land face- or backflat on double-layered, foot-thick mats. Impressive as this was, one worried that someone could get hurt, as the amplified impacts took their empathic toll.

“Kiss the Air” closed with a set of aquatic pieces, including “Wave” and “Kiss the Water.” The first began inexplicably with the gratuitous dropping of six orange wrecking balls onto enclosed cinder blocks, which were duly pulverized. Perhaps if there were Newtonian reactions, such as performers popping up in response, these violent allegories would’ve made sense. As it was, the blocks’ destruction was a non-sequitur, except to add dramatic flourish, or maybe impress the audience’s 8-year olds. “Kiss the Water” itself involved two male performers outfitted in Noe and Ivan España’s bungee rigs yo-yo-ing from overhead horizontal superstructure to water, and interacting with two earthbound female performers in the pool, which contained about 2” of water. Then the lights abruptly went off and it was over.

Although there were no sequined ladies standing atop circling horses, dogs on hind legs wearing hats, or cats leaping through flaming hoops, watching “Kiss the Air” was most like the dimly remembered experience of watching circus aerialists, that is, of being entertained by feats of human agility and nerve (Philippe Petit famously said that falling “wasn’t a possibility”). So was it dance, or art? It was, without debate, strebbing—the wall-crash gerund that Streb’s name has famously become. Its choreographic and artistic roots were recognizable: Trisha Brown’s 1970’s building- and wallwalking (recently re-enacted on-site at the Whitney); the chaotic collisions of Steve Paxton’s “contact improvisation,” recently reshown at MoMA; Burden’s gunshot extremism and Abramović’s puncture wounds. Given Streb’s interest in physics, there were no doubt multiple calculations required to ensure that no humans would be harmed in its performance. Still, its “anti-intellectuality” was oddly dissatifying, and it would’ve benefitted from a 15-minute edit. Although it mightn’t be up to our creative expectations of Streb, it was polished and incessantly in motion, which our primitive brains apparently find irresistibly stimulating. What’s the harm if Streb wants to please the crowd while simultaneously conducting experiments in human musculoskeletal mechanics?

* * *