by David St.-Lascaux

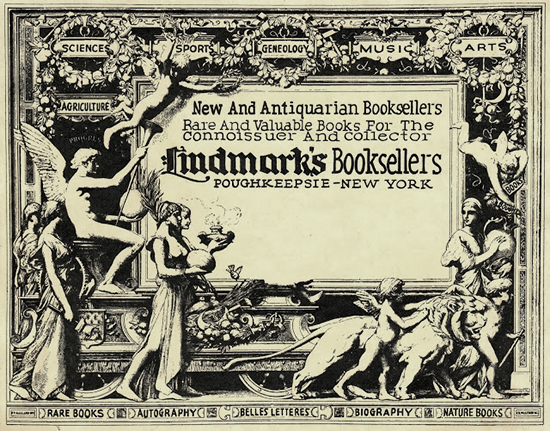

Bookplate, Lindmark’s Booksellers.

13 June 2014

I’VE ONLY EVER PASSED THROUGH Poughkeepsie, probably on the way to and from Rhinebeck, whose Old Rhinebeck Aerodrome Museum has ongoing air shows featuring barnstorming biplanes and other early aircraft. So that, so far, I don’t know much about the city, other than that its appellation is a Wappinger place name, and that its seal features a conic beehive which, sure enough, symbolizes the self-promoted “industry” of the “Queen City” upon its incorporation in 1854. Earlier busy bees were New York’s founding fathers, who convened there to ratify the United States Constitution in 1788.

ASIDE: As it happens, I own an Art Deco-period cobalt blue mirror. This, naturally, relates directly to the blue-and-white Seal of Poughkeepsie, which reflects the city’s Dutch roots. The blue in Delftware is indeed of cobalt origin, as is the blue in Chinese “china.” The history of cobalt as decorative colorant is ancient: the Mesopotamians and Egyptians used it; later, the Chinese to decorate their secret-recipe porcelain (they also kept the method for papermaking secret – for five centuries, a rather better record than American companies in ceding our trade secrets and processes to China at the turn of the Twenty-first); and eventually the Europeans in maiolica and the famous Dutchwares. “The Richest Hole in the Mountain,” a Popular Science article by Rafe Gibbs in May, 1952, about Idaho’s Blackbird Mine (closed in 1982, it soon became a Superfund site, having bled arsenic into local waters) also mentioned cobalt as prized “in the 17th century, when invisible ink was fundamental to royal intrigue….” Most directly important, cobalt (Co, atomic number 27), is critical to animal life as an ingredient in vitamin B12, itself critical to brain and nervous system processes.

My desultory armchair exploration of the neighborhood led me to read Hidden History of the Lower Hudson Valley: Stories from the Albany Post Road (2011), a selective regional history compiled by husband-author (and Poughkeepsie Town Historian) Carney Rhinevault and wife-illustrator Tatiana Rhinevault. Hidden History chronicles the demise of Lindmark’s Book Shop on May 23, 1963, a tragedy reminiscent of Ray Bradbury‘s ironically anti-media science fiction novel Fahrenheit 451 (1953). (Bradbury’s publisher found an easier way than burning [451° being the temperature of paper's spontaneous ignition] to expunge his objectionable ideas: it simply bowdlerized the book until Bradbury was put wise by a friend.) Proprietor John Lindmark had established the business with his wife Rachel in 1928, and was a prestigious merchant of rare books.

Books sold by Lindmark included the presumably unburned, semi-hilarious Complete Works/Marriage Guide by Dr. Frederick Hollick (1902), whose cover promised “the diseases of women familiarly explained,” and which contains The origin of life and process of reproduction in plants and animals: with the anatomy and physiology of the human generative system, male and female, and the causes, prevention and cure of the special diseases to which it is liable: a plain, practical treatise, for popular use, by a seeming coincidence also published by David McKay, republisher of Washington Irving’s 1819 Rip Van Winkle in 1921. Marriage Guide was (and likely, remains) in the Yale Medical Library’s Historical Library.

Like Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (1859), Origin of Life (a book-within-the-Marriage Guide-book) contains the words evolution and species. Hollick’s often extratopical compendium, which early on asks and answers the question, “What is Life?,” discusses red snow, asylum-confined shoemakers, the lethal perils of being a (small) male spider, and Turkish shampooing; it closes with a gratuitous illustration of African steatopygia. It also contains a plate entitled “Sap-Gathering in a Canadian Forest,” reminding me of the tapped maple trees at Hubbard Lodge.

According to the Troy Record on January 17, 1963, Lindmark’s “was described as one of the largest book and manuscripts businesses in the world.” Lindmark’s made the news because of a fire on the previous day that, according to Lindmark, caused the “total loss” of the 130,000 volumes he claimed to be on premises. Incredibly, it was the third (or fourth) fire by arson in Po’keepsie (as an early Lindmark ad sited the business) in less than a month; the firebug was never apprehended.

Notably, Lindmark’s was the first high-profile book-burning in the United States since the Library of Congress lost 35,000 books – including about two-thirds of Thomas Jefferson’s previously donated personal library on Christmas Eve – December 24, 1851, the year in which Herman Melville’s Moby Dick was published. Jefferson took the liberty to interpret Francis Bacon’s organizing principles of Memory, Reason and Imagination as his own History, Philosophy and Fine Arts, in advance of Melvil Dewey’s now-deprecating Decimal System of 1876. Jimmy Wales, admirer of encyclopedist Denis Diderot (his Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers published between 1751 and 1772), used the organizing principles of Peter Roget’s delayed-release Roget’s Thesaurus (having completed it in 1805, Roget didn’t have it published until 1852) for Wikipedia (2001+). An alphabetical index for the latter would be most helpful.

THE OTHER MOST FAMOUS book-burning episodes were Girolamo Savonarola’s “Bonfire of the Vanities” (falò delle vanità) on February 7, 1497 (Sandro Botticelli, a Savonarola acolyte, may have voluntarily destroyed his own artwork in a preceding Florentine bonfire in 1492), and the brownshirt-and-university-student feux de joie in Germany in May, 1933, which involved the pillaging of libraries and bookstores for Jewish (e.g., Albert Einstein and Sigmund Freud) and communistic (e.g., Berthold Brecht and Helen Keller – The Story of My Life, her autobiography, was published in 1903 when she was 22) fuel. (Whether from the bellows blast of hot air and flatulence provided in an on-site diatribe by Joseph Goebbels or because its contents were volatile, cinematic and photographic evidence prove that the compilation burned brightly.) Savonarola was ironically hanged and burned in 1498; the Nazis were ironically trumped at the end of World War II, when another, unpublicized bibliocaust (logophiles and lexiconic tourists will also appreciate biblioclasm and libricide [not to be confused with the rude lubricity], the technical terms for the destruction of books by whatever means) was conducted by the Orwellian-, accurately-named Information Control Division of American occupation forces, which identified over 30,000 titles and confiscated and/or pulped millions of Nazi books (presumably to technically avoid the historical obloquy of having burned them) and thousands of artworks in the service of democracy. Honi soit qui mal y pense.

The January fire was actually a thickening of the Lindmark plotline. In 1961, when the State of New York determined to run an arterial highway through his building, Lindmark refused to vacate. After the fire, rebuffing numerous offers to preserve the estimated 50,000 remaining books (revealing Lindmark’s earlier claim of total loss to be grossly hyperbolic), including the Queen City’s offer of storage space and grassroots community initiatives, Lindmark permitted city officials to enter his store on April 25, 1963, and remove its inventory to the street.

This event made national news. The lede in “State Dumps Collector’s Treasured Books in Street,” the UPI story published in Arizona Republic, read: “State workmen, using a dump truck and a bulldozer, hauled John Lindmark’s collection of books and rare manuscripts outside his store yesterday and dumped them in the street.” Poughkeepsie was condemned: In a letter to the editor of the New York Times on April 27, 1963, a reader lamented, “[That] this incident occurred at the close of National Library Week shows we are hypocritical in our profession of worry about why Johnny can’t find interest in reading.”

What happened in the following weeks, as reported by the Post-Standard on May 23, 1963, was shameful: “Authorities said passersby took hundreds of the books and Lindmark said children used stacks of them as slides. Rain and wind destroyed or badly damaged many more.” At that point, the city played the role of legal arsonist: On May 22, the Post-Standard continued, “The city… began burning the books…. A mechanical shovel scooped the volumes from the sidewalk where they had been exposed to the weather for 27 days, and loaded them into two trucks bound for the incinerator. Supt. of Streets Fred Healy, in charge of the burning, said he acted on the instructions of city Manager Kenneth Pearce. Pearce was out of town….”

According to the Post-Standard’s earlier article about the January fire, Lindmark claimed that his collection included “Ernest Hemingway (previously burned by the Nazis) and Mark Twain first editions and books autographed by the late President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Mrs. [Eleanor] Roosevelt.” On April 27, John W. Stevens reported in “Bookseller’s Library Trampled As Shop Makes Way for Road” in the New York Times, Lindmark expressed dismay over the loss of “a manuscript on the career of John Jay, first chief justice of the United States….”

Anglophiles should note that the first Library of Congress was burned in August 1814 by the British, whose troops incidentally incinerated 3,000 no-doubt objectionable books. It may also be noted that Jefferson’s motivation to sell his collection was to pay his debts rather than to act in pure altruism (while sympathetically reporting that Jefferson lost his first library – and home – to fire in 1770). So that the second burning of Lindmark’s books was not the first (or even second) time books were twice-burned in America: for this, Jefferson and Washington, D.C., hold the distinction. In Lindmark’s case, the books were also destroyed by water – from fire hoses in the first case and rain in the second. As incoming United States Poet Laureate Charles Wright wrote in “A Short History of the Shadow” the title poem of A Short History of the Shadow (2002), quoting the New Testament apocryphal, utterly obscurantist, late Fourth century Gnostic Gospel of Philip:

Under the river’s redemption, it says in the book,

It says in the book,

Through water and fire the whole place becomes purified,

The visible by the visible, the hidden by what is hidden.

The reader is free to conduct her or his own exegesis of the above pseudomystic mumbo-jumbo and its likewise sources.

Poughkeepsie’s historical record includes the biography of citizen Matthew Vassar, runaway brewer and founder of Vassar College, with $408,000 in cash in a tin box, and title to the property, in 1861. In a cautionary to long-windedness, Vassar died on page eleven of his farewell speech to the school’s board of trustees in 1868. Vassar’s Springside estate in town, designed by architect and landscape designer Andrew Jackson Downing and associate Calvert Vaux (rhymes with hawks) of Central Park co-design fame, fell into an extended period of decline until its recent, iffy preservation. Its barn, in poetic Poughkeepsiean tradition, was lost to arson in 1969 (the same year as the Bannerman castle fire), – that is, to barn burning.

As to books: Neither censoring, banning, pulping or burning trumps the simpler inaction of not reading – a default definition of “ignorance.” Also that, whatever their merit, ideas – for which books are physical containers, like people, are readily extinguished by those controlling the levers of power. As Jefferson observed, memory is, after all, a synonym for history – what remains until or after the ashes are scattered.

* * *

July 31: Summer Dragons; Quality v. Quantity.

Text copyright © 2014.