by David St.-Lascaux

March 25, 2014

ONE OF THE PLEASURES of advancing age is an increasing amount of available time. Luxuriant time makes learning possible, and if one has curiosity, one will always discover new worlds, both outside and in (in the life of the mind), for example, on printed pages.

As it happens, we as frequently find “old” ideas as thought-provoking as new ones. Old ideas were thought by now-dead people during times different from our own; whether these thoughts maintain continued relevance, i.e., timeliness and timelessness, I suppose, relates to their universality, a complex concept associated with fatalism and cycles.

* * *

ONE OF THE PROBLEMS of civilization is the superhumanly-longevitous amount of time it takes for new ideas to sink in. Despite printing technology and electronic media, unless ideas are presented to people institutionally, they rarely reach more than a few receptive, attuned, or chance-fated ears. The next step, concerted action upon such acquired knowledge – whether merely implemented or revolutionary, requires huge effort in the face of certain, crushing, systemic reaction. We don’t, I say, learn the things we need to know in order to understand and collectively act to optimize our society and our own individual situations.

An example of a concept that ought to be an educational mandatory is the subject of the history of utopian, intentional communities, and continued efforts toward same. Dolores Hayden’s Seven American Utopias: The Architecture of Communitarian Socialism, 1790 – 1975 (1979) is an instructive primer. We found a copy in her schoolhouse during the 2013-4 holiday season. Hayden, whose focus is on architectural and logistical aspects, covers early Nineteenth-century Phalanx, New Jersey, Fourierists; Amana, Iowa, Inspirationists; Nauvoo, Illinois, Mormons; Oneida, New York, Perfectionists; Hancock, Massachusetts, Shakers; Greeley, Colorado, Union Colonists; and the twentieth century Llano del Rio, California, Cooperative Colonists.

The typical misconception about these groups – if anything is known about them at all – is that what’s important about them is that they were failures, and that their common feature was the sexual kookiness of their practitioners. My earlier reading of the late, former West Cornwall, Connecticut, resident Spencer Klaw’s Without Sin: The Life and Death of the Oneida Community (1993) was based on my misplaced, prurient interest in the group’s undeniably unusual sexual practices (rotating partners; forbidden male ejaculation; eugenic breeding). But those who focus on sex and demise, as I did, miss the point: these societies were responses to the devastation that the Industrial Revolution was wreaking upon agrarian and craft cultures, which continues today, with a vengeance, globally. (A little over a hundred years after America’s population tipped into an urban majority, in 2010 the world’s population was, for the first time – revealing a foreboding trend – less than 50 percent rural.) Even more important, they were attempts in the new, post-noblesse oblige, post-monarchic world, to answer the question posed in Luke 3:10-11:

And the multitudes asked [Jesus], “What then must we do? And he answered them, “He who has two coats, let him share with him who has none; and he who has food, let him do likewise.”

The question – What Then Must We Do? – is the title of political economist Gar Alperovitz’s prescriptive 2013 book, in which Alperovitz advocates participation in credit unions, worker ownership of businesses, participatory local budgeting, collaboration by local institutions, community development and land trusts, use of public funds for public good, socially responsible investing, buying energy from public utilities, enlisting the religious community’s support, fighting unemployment – and, as he says, “more.” It’s a good start, noting that Alperovitz is working with the framework of the current system, as opposed, say, to suggesting global, free, lifelong education; the needed, radical global reduction of resource and energy consumption; the final elimination of superstition and tribalism; acknowledgment of, and adjustment to today’s society’s reduced need for “work” – and more, including global demilitarization; global de-industrialization; the elimination of plastic, and concomitant, ongoing global environmental clean-up; the depharmaceuticalization of daily life; and a return to local living. Most important: the long-term institutionalization of organized activity toward sustainability.

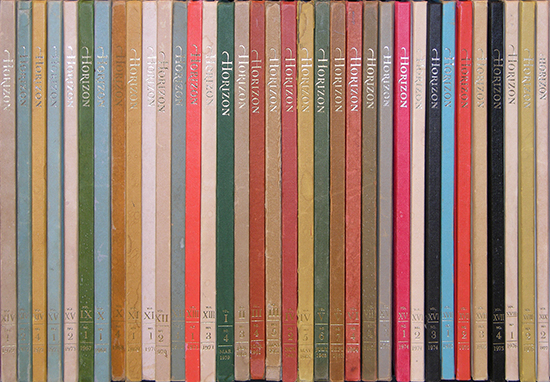

Restocking the Library’s shelves, I unboxed my collection of Horizon magazines, artifacts of the Sixties and Seventies. Among the copies of this beautiful, hardcover magazine was the Autumn 1973 issue, upon whose cover a tipped-on image of a collage by surrealist Max Ernst. The lead theme in this issue, whose opening page essay by Walter Karp and Barbara Klaw (Spencer’s wife) was entitled “More Notes on the Revolution,” was “The Good Life,” documenting intentional communities – from Connecticut’s Heritage Village, a bourgeois retirement development (“We don’t get many weirdoes – they take one look at the place and know they don’t belong and wouldn’t be happy here”) to Sugar Loaf, New York, to live-aboards at the 79th Street Boat Basin.

Horizon presented culture as a random cornucopia; the reader was expected to be omnivorous, and able to partake of unexpected fare at the turn of a page. This issue included the cover story on Ernst, a first-person account of a mugging on the Brooklyn Bridge “in broad daylight,” a Tlingit iron knife featuring a beaver’s head with inlaid abalone eyes, a full-page chiaroscuro monochrome photo of Venus de Milo (c. 130-100 BC), a miniature of Knight Templar Jacques de Molay being burned at the stake, and “Our Forefathers in Hot Pursuit of the Good Life,” by E.M. Halliday, an airily dismissive article surveying the earlier-noted Nineteenth-century communes. Perhaps its editors intended Horizon to produce vivid dreams, or wider brain stimulation.

THE LAST WORD on utopian communities is that one did succeed – spectacularly, and thrives today: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter‑day Saints. If Joseph Smith’s life was cut short by a mob, his successors, led by Brigham Young, were savvier, and more tenacious. The Book of Mormon may be unreadable (I’ve tried: its plotless glop is numbing), but the wingless Angel Moroni sounds his clarion (and note poet Charles Simic’s hilarious “In the Library,” which conjures a Dictionary of Angels), standing gilded atop Mormon temples throughout the Land of the Free, proving that you don’t need to believe in something in order to recognize its tribal efficacy.

* * *

April 26: Invasive Species, World’s End

Text and photo copyright © 2014