Interrupting Infinity Exclusive Commentary. © 2012 by David St.-Lascaux

12 September 2012

Regarding Warhol: Sixty Artists, Fifty Years

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, September 18-December 31, 2012

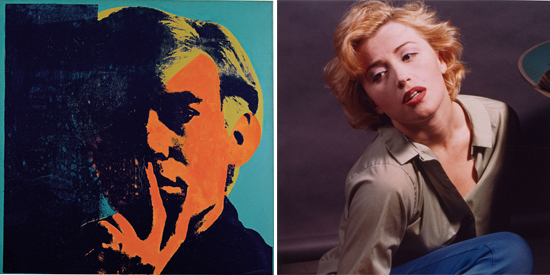

Andy Warhol, “Self-Portrait” (1967); Cindy Sherman, “Untitled” (detail; 1982). All images courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

THINGS SURE WERE MOVING FAST in the 60’s. The glibly, misnamed Pop Art movement (which had originated in the 50’s) was ramping up in the U.S. and U.K. as the decade began, along with the ongoing megashifts: the multi-decades’-long-simmering civil rights movement, American overreach in Vietnam, birth control and women’s rights, and so much more. It seems the present tense is always in flux.

Two things that weren’t new in the 60’s were American consumerism and celebrity worship. Both phenomena were well in place, although the postwar period could be said to be supercharged by electronics (e.g., TVs and transistor radios), which fueled the media through which advertising – the driver of unnecessary, ideological consumption – and entertainment – the insatiable hunger for novelty and escape – were massively distributed.

Regarding Warhol: Sixty Artists, Fifty Years, the new exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, presents Andy Warhol – through the lens of his own work and that of selected contemporaries and descendants – as an artist who mined the twin American fool’s goldmines of mass consumption and the cult of celebrity. The show provides two major insights: First, it exposes Warhol’s celebrity worship as his ultimate artistic and societal contribution, and second, it documents the vast number of derivative artists he engendered, most of whom we may now entirely dismiss.

Andy Warhol, “Brillo Box (Soap Pads)” (1964); Ai Weiwei, “Neolithic Vase with Coca-Cola Logo” (2010).

The show appropriately gives short shrift to Warhol’s consumer-related works (although Ai Weiwei’s terracotta “Neolithic Vase with Coca-Cola Logo” [2010] send-up is hilarious, and the ironic question of whether the Campbell’s Soup Company or the Andy Warhol Foundation had the upper hand in their belated intellectual property negotiations bears footnote interest), given that he was neither an original innovator nor committed to defending his inspired ready-mades from ensuing controversy. In fact, Robert Rauschenberg’s “Monogram” (1955-9) and Richard Hamilton’s pioneering “Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing?” (1956) both predated Warhol’s consumer imagery; and James Rosenquist’s vastly underappreciated “F-111” (1964-5), which connected consumerism to empire, revealed Warhol’s “Brillo Box (Soap Pads)” (1964) to be intellectually trivial.

A claim that Warhol was commenting ironically about celebrity culture is exposed false by his single-minded cultivation of self-celebrity; he was a quintessential “Me Generation” mentor who understood the zero-sum principle of “winner take all.”

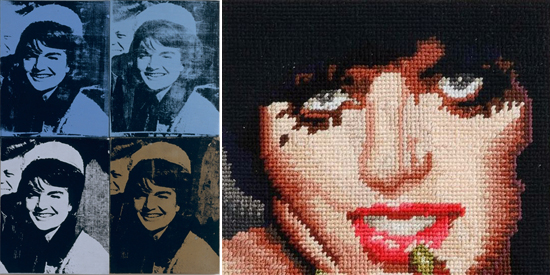

Cults of celebrity were already centuries-old when Warhol rediscovered them. Fred Inglis’s A Short History of Celebrity, quoted in Joyce E. Chaplin’s introduction to Benjamin Franklin’s Autobiography, reveals that Isaac Newton and Benjamin Franklin were both publicly adulated. The Nineteenth Century’s numerous lyceum lecture-circuit luminaries included Mark Twain and Charles Dickens. Following this line, Regarding Warhol makes the case that Warhol’s celebrity imagery is his main contribution to art. Whatever his other endeavors, Warhol was undeniably the artist who first exploited the national obsession with celebrity in a manner most offensive to the intelligentsia. It may very well be true that Elvis Presley and Marilyn Monroe were extraordinary entertainers, and that individual identity-crushing mass society needs the palliation of surrogate “stars.” It is certainly true that their silkscreened portraits are more famous fifty years later than their celluloid flickerings, because these are arresting, simple block book faces for tube-agog illiterates, displacing the dashboard statuettes of Jesus and Mary. It is also true that the morbid appropriation of the merely months’-dead face of Monroe (or even more obscene, the smiling Jacqueline Kennedy sitting in the open Lincoln limousine minutes before her [also-smiling] background husband’s assassination) really was as despicable and crass as it must’ve seemed to contemporary critics. Warhol’s alignment with the low-culture masses must’ve infuriated the high-culture arbiters of the Dwight Macdonald school, who were reveling in the intellectually transcendental possibilities of abstract art as a cultural quantum leap forward – as finally touching G*d, which Pop and Beat entirely derailed. Alexander Calder’s mobiles – or Agnes Martin’s Zen compositions – Warhol’s sign-shop portraits were most definitely not. The argument that they were anti-progressive and even civilizationally regressive is valid for the same reason that Marcel Duchamp’s reactive “Fountain” (1917) was conversely neither, namely the horrific context of World War I, a mass cultural field day in which 100,000 were gassed and 16 million killed, including 7 million civilians. Duchamp’s contemporaries, the complex, controversial Gertrude Stein and Érik Satie, also inarguably advanced the conversations in their respective fields.

A claim that Warhol was commenting ironically about celebrity culture is exposed false by his single-minded cultivation of self-celebrity; he was a quintessential “Me Generation” mentor of self-aggrandizement who understood the zero-sum principle of “winner take all,” and that fame is engineered through endless name repetitions, media citations and, posthumously, museum retrospectives. Warhol promoted celebrity culture in three ways: through his starfucking celebrity portraits, through his relentless personal aspiration to celebrity status, and through his disingenuous, manipulative use of would-be “superstar” seekers of fame for source material (R.I.P. Jean-Michel Basquiat), to extend his “brand,” and to promote the myth of celebrity without effort or merit. Today, we live with the actualization of his vision in a society in which Americans reflexively lust for attention rather than to make useful contributions to society. The waste is colossal.

The show really hits stride in its presentation of derivative works, although the inescapable conclusions are cruel. These works make only too manifest why the vacuous output of their creators is so natively suited to middle school art exhibitions and yawning landfills.

Regarding Warhol’s second contribution to our understanding of Warhol’s legacy is its assembly and exhibition of Warhol’s contemporaries, as well as myriad later imitators, the latter whose subsequent aggregate contributions to art are, we now see, zed. The show’s technique of intermixing these works is logical, if flawed in execution. For example, the inclusion of contemporary work is erratic, arbitrary and omissive. While works by John Baldessari, Hans Haacke, Hans Richter and Ed Ruscha are enlighteningly shown, the most obvious and appropriate examples – Hamilton, Roy Lichtenstein, Jasper Johns, Claes Oldenburg, Rauschenberg, Rosenquist, and photorealist Audrey Flack, to name a few, are inexplicably missing. Contrasting works by such artists as Helen Frankenthaler, Martin, Kenneth Noland and Mark Rothko, which would set Warhol’s oeuvre in high relief, are also missing (though present in adjacent galleries). In fairness to the curators, it’s not possible to present an exhaustive comparative catalog, and Warhol was nothing if not complex.

Andy Warhol, “Nine Jackies” (detail; 1964); Francesco Vezzoli, “Liza Minnelli” (detail; 1999).

The show really hits stride in its presentation of derivative works, although the inescapable conclusions are cruel. Regarding Warhol strangely, if aptly, opens with the 1992 Esquire magazine cover by Barbara Kruger of Howard Stern, proclaiming “I hate myself” in three red bars. To say that Kruger’s coincidentally unoriginal (i.e., plagiaristic) verbal encomium to Stern damages her feminist credibility and legacy would require an infinitely-regressing redefinition of the word “understatement.” Maybe this is the intention of the curators: to present the artists following Warhol as low-culture copycat losers. If so, they have succeeded. Jeff Koons comes across as a clown whose vile if visually seductive work, which he attempts to spin as calculated “banality,” elicits shudders of disgust. Cindy Sherman personifies the solipsistic vortex into which “it’s always all about me” ultimately leads. Francesco Vezzoli’s crocheted “Liza Minnelli” (1999), Karen Kilimnik’s pastel-colored Paris Hilton in “Marie Antoinette out for a walk at her petite Hermitage, France, 1750” (2005) and Elizabeth Peyton’s “Blue Kurt” [Cobain] (1995) make only too manifest why the vacuous output of their creators is so natively suited to suburban lawn blanket tag sales, strip-mall flea markets, middle school art exhibitions and yawning landfills. It was a serious error for the activists Glenn Ligon and Haacke to permit inclusion in this fool’s gallery, although their work – notably Haacke’s knockout “The Right to Life” (1979) and Ligon’s “Malcolm X (small version 1) #1” (2001) – eclipse everything Warhol, and pretty much everything else in the exhibition.

It must’ve been a huge relief to the corporate and political powers at the time that the culturati were debating whether product packaging was art as opposed to the ramifications of an entertainment-dominated culture. Warhol’s promotion of egocentricity and diversion was – and is – the capitalist leaders’ fondest dream.

The show also presents a bonus revelation: That the art establishment avoided – and avoids – the hard questions. Warhol’s contemporary critics didn’t choose to focus on consumerism, but rather on perceived æsthetic heresy, utterly failing to concern themselves with the real social issues putatively raised. It must’ve been a huge relief to the corporate and political powers at the time that the culturati were debating whether product packaging was art as opposed to the cost of empire, burgeoning industrial pollution, the merits and ramifications of a consumer-driven economy and an entertainment-dominated culture, whether Blacks were “men,” women more than chattel, or gays due other than chemical neutering or imprisonment. Thus, Regarding Warhol is most telling in its omissions, failing to ask the obvious, hard questions, including:

Why didn’t Warhol produce a series on the Vietnam War, which had all the ingredients he extolled, and which dominated the media he cherished during the entire pre-Ronald Reagan phase of his career?

Exactly what “fascinated” Warhol about civil rights protests?

Where were Warhol’s portraits of celebrity feminists – Betty Friedan, Germaine Greer, Gloria Steinem and Erica Jong?

Given Warhol’s homosexuality, why didn’t the Stonewall riots get his passing nod?

What does the ascent and dominance of celebrity culture imply about the Met’s own collections, which offer a comprehensive showing of often-anonymous human imagination, diversity and creativity – the canonical paradigms of culture? It would’ve been something to see some of the Met’s historical portraits of emperors, merchants and peasants contrasted with Warhol’s Kennedy and Wolfgang Tillman’s John Waters.

While resorting to conspiracy theory to answer the above questions might seem – on its face – paranoid, Gary Indiana’s documentation of MoMA-connected government propaganda, including the postwar co-option of art for “the propagation of the free-enterprise system” in Andy Warhol and the Can that Sold the World provides logical closure. Whether Warhol was latterly “incentivized” through access to clients and the White House, his promotion of egocentricity and diversion was – and is – the capitalist leaders’ fondest dream.

Of course, the above questions are not meant suggest to that Andy Warhol was a deficient man; far from it. He was a towering talent, an innovative genius, a documenter and reflection of his time, an excessively hard worker, a prolific producer of an impossibly diverse body of multimedia art, and a challenger of convention. Warhol has disingenuously been mythologized as nonjudgmental – he simply reported, we are told; it’s up to us to be the deciders. Imitating Warhol and his imitators, the Met tries to avoid passing judgment, but the works speak loudly for themselves. Upon seeing Regarding Warhol, a viewer is able to unambiguously understand Warhol at last – to have corroboration, if it was ever in doubt, of Warhol’s personal value system, namely that he sought celebrity; and to confirm, if it wasn’t entirely obvious, that Warhol has been ever so widely imitated both during his lifetime and after his death. His considerable merits aside, what he celebrated was bankrupt, and those who followed him haven’t the excuse of originality, messages this show mercilessly drives home.

* * *

Regarding Warhol: Sixty Artists, Fifty Years, on exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, September 18 – December 31, 2012. Information at the Met Museum website at this link.

* * *